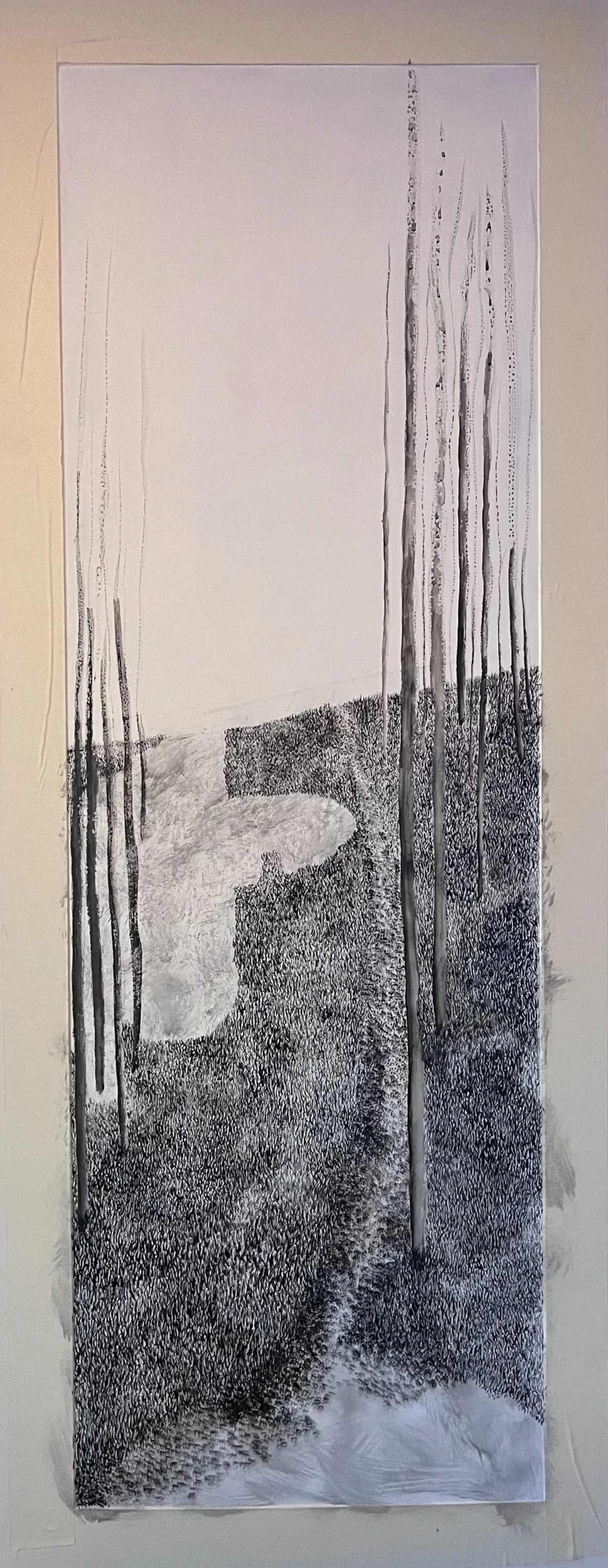

“Understory”.

The World Is your Canvas.

The office where I work has recently been undergoing renovations as we expand to make more room for our growing team and needs. Unexpectedly, this presented the perfect opportunity for me.

At the start of January, while a few of us braved the office amidst ongoing renovations, my workplace offered us the chance to take home the old pictures that once hung on the walls. This sparked an idea - what if I took one, or even two, home with me to paint over and use as a sort of makeshift canvas?

As it happened, I was in the office that day and managed to get first pick. I selected two pictures of a similar size with a relatively robust surface and frame. They were also both around 110cm by 35cm, which in my thinking, would make them slightly easier to manoeuvre on the bus home that evening. What I hadn’t anticipated was the wind turning the two pictures into sails as I wrestled them along the street to my bus stop. Thankfully, when the bus arrived, I managed to grab a seat near the front for the ride home.

Once I got them home, my initial plan was to remove the picture from the frame and paint over it with some leftover emulsion from touching up the kitchen (after I had accidentally painted the wall black while working on Scaling Up #1). This was relatively smooth sailing - except that the foam board with the picture was glued or secured to the mount, meaning I had to adjust my approach. Instead, I masked around the mount and painted over the image while it remained in place.

It took three coats of emulsion to get a relatively clean base. Some areas still reveal traces of the original blue toned image beneath, which I like - the extra layer alludes to the history and journey of this piece, its evolving energy. I also intentionally painted each coat in different directions to add texture, alternating between vertical and horizontal strokes to mimic the grain and surface of a traditional canvas board.

Two days later, with the emulsion fully dry, the real work was about to begin. My plan for this piece was based on an earlier sketch I had made from one of my photographs of the woods around Loch Tay in the Scottish Highlands. I also wanted to experiment with the Chinese painting set my brother had gifted me for Christmas, incorporating the techniques and processes I had been studying in The Art of Chinese Brush Painting.

While I was initially excited to use my new painting set, I have to admit that patience isn’t always my strong suit - something I quickly realised when grinding down the ink stick. I struggled to achieve the depth of colour I’m used to working with, and to make matters worse, the ink was repelled by the emulsion base more than I had anticipated. This growing frustration set the tone for the early stages of the painting.

Originally, I had planned to paint the trees first to help structure the composition and orientate myself. However, with the ink refusing to adhere properly, I decided to switch to my stipple brush and use the ground ink liquid for a wash where the ground cover would eventually be. This adjustment helped; when I later added details to the ground cover, the ink adhered more easily to the pre-washed areas while still being repelled in places - something I had wanted to experiment with since reading The Art of Chinese Brush Painting. The book had mentioned this as a technique, and I was intrigued by how it could echo the hazy nature of memory - the way we fill in gaps, much like a viewer projecting their own thoughts and recollections onto a painting. Even across language barriers or cultural differences, this shared act of interpretation allows us to experience an emotional reverence for a piece and the place it depicts.

While I initially struggled to grind the ink stick down to the depth I usually prefer, the process eventually grew on me. It forced me to slow down and observe my painting more carefully - something I wouldn’t normally do when using pre-bottled ink. This extra time gave me space to consider the techniques I was experimenting with and reflect on how they were taking shape.

For example, I decided to take more time painting the tree trunks on the right-hand side. These were slowly layered with the ground ink, letting each layer completely dry before going in with the next, creating a different texture and an almost shadowy effect - some trees are barely visible at all. In contrast, the trees on the left-hand side were primarily painted with pre-bottled ink. While I still like the effect, they have a distinctly different energy and presence compared to those on the right.

This contrast plays into the themes of memory and belonging. Some memories remain vivid, sharp in detail, while others fade, requiring us to fill in the gaps through interpretation or the recollections of others. The differing treatments of the trees reflect this - one side more defined, the other more elusive, like fragments of memory shifting between clarity and obscurity.

In The Art of Chinese Brush Painting, the author discusses the importance of balance in Chinese painting - the idea that blank space, or areas left unpainted, are just as significant as those filled with ink. While I wouldn’t say this painting fully captures that delicate balance, I did intentionally leave the sky empty and use a light ink wash for the tops of the trees to create a faded, almost distant effect.

This choice was also an attempt to reflect how memories function - things further away, whether in distance or time, often become hazier and harder to recall, while those closer to us feel sharper, carrying a more intense energy and presence. By allowing the trees to dissolve into the empty space, I wanted to evoke that sense of fading recollection, contrasting it with the weight and density of the foreground.

The title of this piece, Understory, comes from the word referring to “the (layer of) vegetation growing beneath the level of the tallest trees in a forest.” I first came across the word while reading Belonging by Amanda Thomson, where it appears within the first few pages. The book, a personal memoir, explores themes of family, identity, and how natural landscapes shape who we are.

I happened to start reading it while working on the ground cover beneath the trees in this piece, and the coincidence felt too significant to ignore. Understory became the perfect name, encapsulating not only the visual layers in the painting but also the deeper themes of memory, place, and connection that run through both my work and Thomson’s writing.